Children’s Historical Fiction in Ten (+1) Quotes

1. ‘History is more or less bunk’: Henry Ford

As good a place as any to start. Children’s historical fiction has never been that popular with readers or critics. It’s had its days, of course. The library of any self-respecting middle-class English household at the beginning of the twentieth century would have had a good shelf of G.A. Henty. And what a gap there would be in the Carnegie Medal winners from 1954–1980 if all the historical novel winners were ruled out. But where were the historical novels in the Carnegie of Carnegies top ten list of all-time medal winners in 2007, only Robert Westall’s The Machine Gunners (1975) getting in?

‘Won’t historical fiction just disappear?’ John Stephens might have asked in 1992, in his ground-breaking critical study Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction. What he actually wrote was: ‘A highly technological and extremely acquisitive society, with great personal mobility and information resources, tends to look, if it looks at all, elsewhere for the exotic than in a past which seems scientifically ignorant and technologically undeveloped’ (pp.203–204). Even 1992 now seems just that way, no smartphones, Facebook, or YouTube: how quickly the present becomes the past. Anyway, it’s a brave statement but maybe a bit foolhardy. Step up Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall (2010) or George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones (1996) (medieval power struggles dressed up with dragons) or even Jennifer Worth’s Call the Midwife (2011). Not written for children, but continuing evidence of the fascination of the past. And when we read about the past are we just looking for ‘the exotic’?

2. ‘The Beastly Best Bits: The Executioner’s Cut, Straight to the Bone, Only the Most Murderous Moments in History’: Horrible Histories

Talking of the exotic appeal of history …. Weirdly, just a year after Stephens’ prediction of the end of history, Terry Deary’s Horrible Histories were launched, to become the most popular children’s history series ever in Britain. And it was based exactly on how different – bloodier, smellier, nastier, stupider, crazier, more disgusting (indeed how much more ignorant and undeveloped) the past was than the present. And ‘teachers love ‘em because they’re stuffed with TRUE facts’. Did Scholastic make that distinction between TRUE facts and all the other kind of facts even before

Trump, I wonder?

Or maybe, in a sense, it is actually fiction. For, by leaving out ‘the boring bits’, you necessarily create a particular view of the past. You might think, too, that Horrible Histories imply a possibly perfect present. Except, translated into a TV comedy sketch programme that jumps joyfully from the Stone Age to suffragettes, it seems to stress more the abiding absurdity of human behaviour.

Well, there are many here among us who feel that life is but a joke.

3. ‘Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it’: George Santayana

Now that’s a scary thought for readers of Horrible Histories (and even scarier for those who don’t read them). It taps into what I believe to be a crucial aspect of historical fiction, whether for adults or children, but especially for children: its educative function. Yes, it’s literature. Yes, you can enjoy it. And yes, you might learn from it. There isn’t any necessary contradiction.

And learn not just about the particular material differences of another time and place (for a different time implies a different place, see 6), but different ways of looking at the world and what you might learn from them.

And it’s always been the case. All those recent books about the First World War for children, aren’t they intended to convince their readers of the horrors of war? Henty and his imitators a century before, entirely to the contrary, wrote about war to convince children (boys) of the adventure, honour and glory to be won in serving your country. Different times, different messages; and, for better or worse, both using an argument from history.

Santayana implies a view of the past as not just different but disastrous. Otherwise, why would we be ‘condemned’ to repeat it? But, for some children’s writers and readers, the past is a rather magical place. A misty rural nostalgia bedews some classic titles: Philippa Peace’s Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958) and Lucy Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe (1954). Not strictly historical fiction but certainly about the relationship of the present and the past. And how many of the books about the First World War still suggest that soldiers went straight from the sunlit Edwardian countryside of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) to the trenches: a version of a lost Downton Abbey Eden? When mostly they went from the cities where the majority of the population lived by then.

Kipling, and Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906), as the founding father of a strain of British twentieth-century children’s historical literature, turning away from Henty’s imperial wars toward English names and English places. Folky yes but also ordinary and immigrant, waves of early invaders becoming one people, and so on to Rosemary Sutcliff on the conservative road, and Geoffrey Trease and Robert Leeson on the radical.

But what might Kipling be getting at here? What’s the difference between history and stories? Not much say some. Isn’t history a selected version of the past, arranged with characters and a plot? Even eyewitness accounts of contemporary events are unreliable. Everyone has an axe to grind. Memory is selective. Subjectivity is piled on subjectivity. We always look back from where we are and the landscape is different from there. So is history really a form of fiction?

Not quite. The past happened and is unalterable (leaving out time machines). In some situations, the circumstances of the past may be unclear. As Wellington said of the chaotic battle of Waterloo: ‘It is impossible to say when each important occurrence took place, or in what order’. But that was a battle and even then, finally, it was clear who’d won. A large amount of who did and said what in the past is clear and uncontroversial. But the study of history is speculation about ‘the how’ and ‘the why’ and what it means. And the evidence has to be cited (so that someone else can go and check it’s right) and arranged as a convincing argument. And it’s never the final word. Someone will disagree, often violently. Does anyone remember David Baddiel and Robert Newman’s history professor sketches in the 1990s? That’s your past that is!

But a story is a story, it doesn’t have footnotes. It doesn’t need to discuss (writing on both sides of the paper), give space to opposing arguments or acknowledge other possibilities. It can create an illusion of events unfolding as they might have done. And it isn’t confined to selecting from evidence, it can make things up and leave things out, fill in gaps, create new people and new events – and have a time machine, as long as it’s used only to get you there and back (see 5). Back to Kipling, it can grip its audience as only a story can. It can give us more of a sense of being in the past than history itself. So –

5. ‘The past is really almost as much a work of the imagination as the future’: Jessamyn West

Yes, and no. Yes, because creating the illusion of a living past requires at least as much ingenuity as creating a fantasy world and, like any good fantasy, it has to respect the rules of that world, its limits and possibilities. The difference being that, with historical fiction, the limits and possibilities are, to a greater or lesser extent, set for you. Particularly the limits of the material world. So no, you can’t have a television in the corner of a sixteenth-century room, and sit on a sofa and eat crisps, that’s fantasy. And you can’t drink coffee or tea in Britain before the seventeenth century, that’s poor research (unless you are very clear about how you are enabled to do something that most other people can’t and don’t).

Cultural and social life, how people in the past related to one another and what they believed, are necessarily rather more malleable ….

6. ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there’: L.P. Hartley

Surely the most famous quote about the past, and deservedly so. It suggests so much. The difficulty of understanding a different way of seeing the world and behaviour. The past is a place with its own way of talking and customs, and you come to it as a bemused outsider. You cannot be part of it as a native can. And yet it is not entirely another planet, you can visit it as a traveller (or in memory, as Leo does in The Go-Between (1953), perhaps with a guide and a phrase book (or, in Leo’s case, the benefit of hindsight), you can note the differences and the similarities with your own way of life, the way it confirms and confounds your expectations.

The relationship between past and present and the idea of the visiting traveller is the stuff of all historical fiction, but perhaps especially children’s historical fiction. The time-slip story, if not invented by writers for children, has been their especial preserve.

There is a question generally for writers of historical fiction: how to depict opinions and practices in the past that now seem at best reprehensible and at worst barbaric, but were a characteristic of their time. Can you portray a slave holder as honourable, principled and even heroic? US presidents Washington and Jefferson both owned slaves. Can you conceive of a sympathetic Roman character who enjoys games at the amphitheatre in which people and animals are routinely slaughtered? This is possible for a nimble adult writer for an adult audience: witness Hilary Mantel’s rehabilitation of Thomas Cromwell, while taking down Thomas More (Wolf Hall). But for a children’s writer, surely there has to be some hand holding?

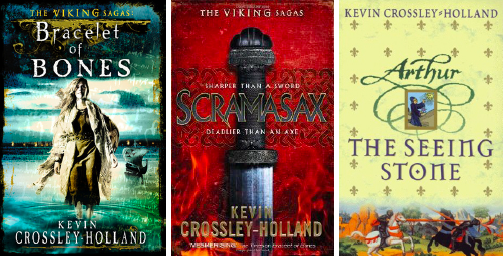

The best hand-holder writing historical fiction for children presently must surely be Kevin Crossley-Holland. And he does it by going boldly where it is historically dangerous to go. Books about a Viking girl, who leaves home and travels across Europe to find her father in Constantinople and then sets off on campaign with him in Bracelet of Bones (2011) and Scramasax (2012). Surely this is historically implausible? Would a young woman in Viking times have such freedom? And yet such is Crossley-Holland’s knowledge of his subject, the detail he has at his fingertips, and the careful way in which he shows that Solveig’s journeys are dependent, as they would have been, on male permission and assistance, make it entirely credible. And, as in his Arthur trilogy (The Seeing Stone (2000), At the Crossing Places (2001), King of the Middle March (2003)), Crossley-Holland uses the cross-cultural (is there a word for bridging times that is not timeless?) notion of children seeing things differently from adults (and women from men) as a means of creating critical viewpoints for a modern child reader within the stories.

And the point of the Twain quote is that it is always dangerous to give way to generalities or current orthodoxy (the plausibility of fiction) when thinking about human behaviour, especially in the past. Sometimes fiction can anticipate the general public’s perception of history. Anyone watching the recent David Olusoga’s Black and British: A Forgotten History (BBC Two, 2016) might have been astonished by the continuing black presence, but less so if they had read Marjorie Darke’s trilogy from the 1970s and 1980s tracing the descendants of a freed slave in twentieth-century England (The First of Midnight (1977), A Long Way to Go (1978), Comeback (1982)). Or Bob Leeson’s trilogy from the same period (Maroon Boy (1973), Bess (1974), The White Horse (1977)). But then …

8. ‘History isn’t about dates and places and wars. It’s about the people who fill the spaces between them’: Jodi Picoult

It can be about both. And surely the greatest historical novel, Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) is about both. But, as Picoult says, the interest in the novel is in the largely invented characters whose lives are affected by the great events. Not to say you can’t write novels about the movers and shakers: Wolf Hall again. And there much of the interest is in the political machinations themselves: as if we don’t know the outcomes and there is everything to risk and play for still. A brilliant example of the way that history can be made to live in a novel.

Children’s historical fiction used to concern itself with famous men [sic] but now largely doesn’t. From the twentieth century, whether written from a left, liberal or conservative viewpoint, it’s been about ordinary people, sometimes caught up in extraordinary events, but sometimes just making their own way in another time. A movement in literature that seems to move in parallel and sometimes crosses with the development of social history in the academic discipline.

9. ‘Facts get their importance from what is made of them in interpretation … for interpretations depend very much on who the interpreter is, who he or she is addressing, what his or her purpose is, at what historical moment the interpretation takes place’: Edward Said

Literature, like the study of history itself, is concerned with interpreting the past, and, arguably, has greater freedom to do so. As John Stephens noted back in 1992, historical fiction has a high ideological component. He didn’t think that was necessarily healthy. Yet it has meant that children’s historical fiction has been a means of discussing social and political questions with young people in a way that, for a long time, children’s books set in the present rarely tackled.

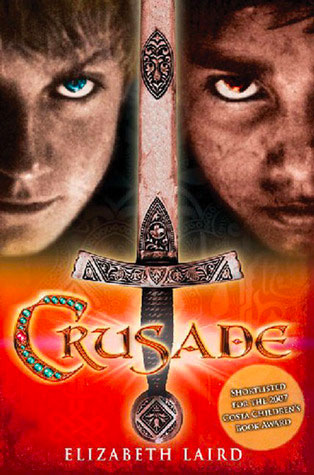

And this discussion moves with the priorities of the time in which it is written. It can be no accident that after the Second World War, which marked the end of empire, so many historical writers for children turned inward to look at English history and, in the 1960s and 1970s, to bring contemporary concerns with racial justice and feminism into their books. And, more recently, children’s historical fiction has moved out into the wider world again. Perhaps most strikingly in its consideration of aspects of past contacts with the Islamic world: Elizabeth Laird’s Crusade (2007) or Kevin Crossley-Holland’s Arthur trilogy and Gatty’s Tale (2006)) (again, he really is remarkable).

10. ‘I’m interested in the way in which the past affects the present and I think that if we understand a good deal more about history, we automatically understand a great more about contemporary life’: Toni Morrison

It seems to me that children’s historical fiction is more about heritage than it is about history proper. There is an element of heritage in any consideration of history. What is of interest in the past is what it reveals about the present, what it tells us about who we are (or who we think we are). This is sometimes a conscious process (I will write about the enslavement of Africans because black rights are an issue now), but it doesn’t need to be. It’s just that what concerns us about the present political and social shape of the world naturally feeds back into historical preoccupations.

We look for a history that enlightens our contemporary view of the world. And this can be contentious. Witness the campaigns to remove the Rhodes memorial from Oxford University or to rename the Colston Hall in Bristol. These are not so much arguments about what actually happened, but about who and what we should honour from the past. And if we look back at the history of children’s historical fiction, and those other children’s fictions that deal with the relationship of past and present, this is almost always a primary consideration, implicitly or explicitly. It is part of a dialogue in which adults set out the shape of the world for children: of what they think is good and honourable and what is false and destructive. The questions that have faced people in the past, the questions that face us now and those that face us in the future are as much a continuum as they are a series of disjunctions.

11. ‘History is, in a sense, a story, a narrative of adventure and of vision, of character and of incident. It is also a portrait of the great general drama of the human spirit’: Peter Ackroyd

A proper subject for literature …

Boston, Lucy. The Children of Green Knowe (1954). London: Faber & Faber.

Crossley-Holland, Kevin. Bracelet of Bones (2011), Scramasax (2012). London: Quercus.

–– The Seeing Stone (2000), At the Crossing Places (2001), King of the Middle March (2003) (Arthur trilogy). London: Orion.

–– Gatty’s Tale (2006). London: Orion.

Deary, Terry (illus. Martin Brown). The Beastly Best Bits: The Executioner’s Cut (Horrible Histories) (2013). London: Scholastic.

Darke, Marjorie. The First of Midnight (1977), A Long Way to Go (1978), Comeback (1982) (trilogy). Harmondsworth: Kestrel.

Grahame, Kenneth (illus. E.H. Shepard). The Wind in the Willows (1908). London: Methuen.

Hartley, L.P. The Go-Between (1953). London: Hamish Hamilton.

Kipling, Rudyard. Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906). London: Macmillan.

Laird, Elizabeth. Crusade (2007). Basingstoke: Macmillan Children’s Books.

Leeson, Robert. Maroon Boy (1973), Bess (1974), The White Horse (1977) (trilogy). London: Collins.

Peace, Philippa. Tom’s Midnight Garden (1958). Oxford University Press.

Westall, Robert. The Machine Gunners (1975). Basingstoke: Macmillan Children’s Books.