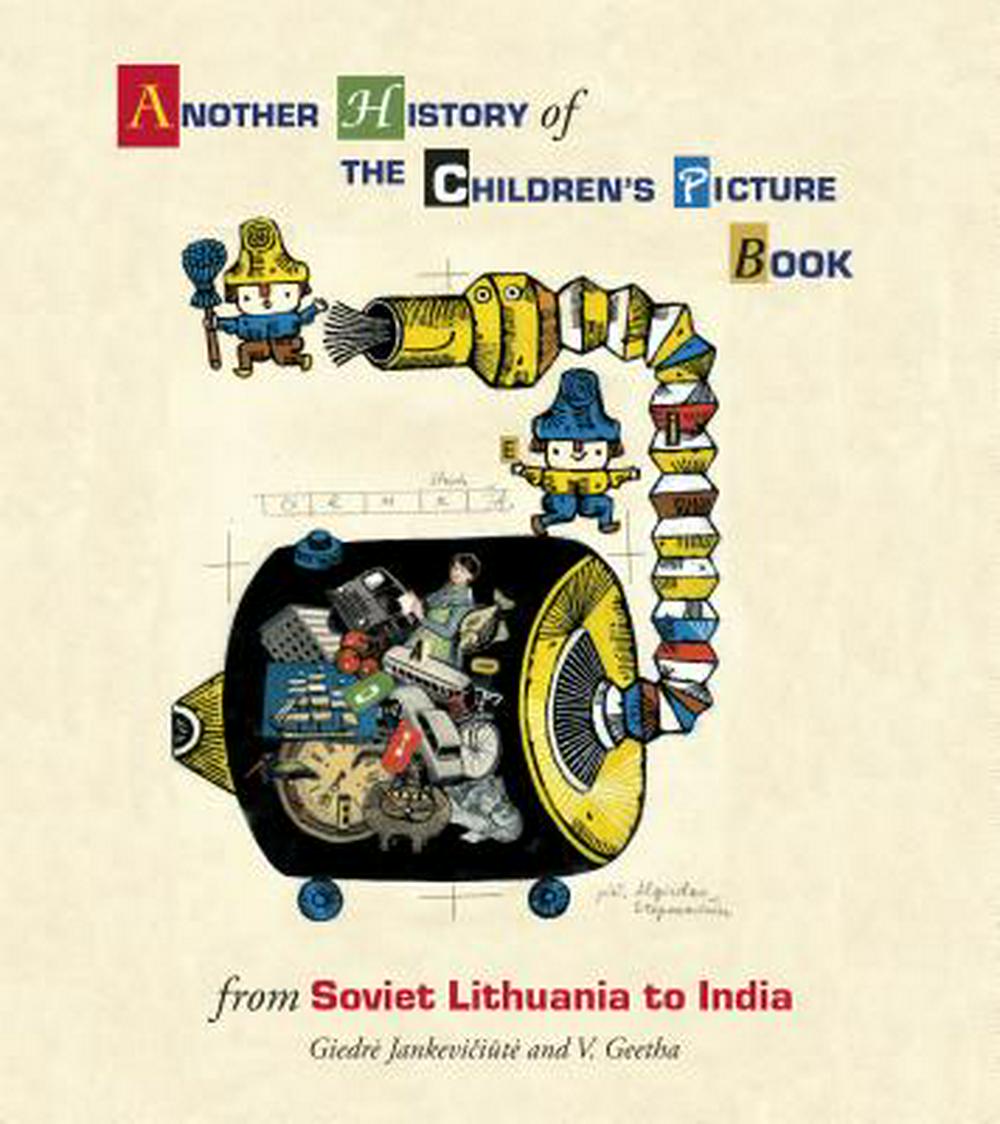

Another History of the Children’s Picture Book

What drew you both to this project?

Working with the Lithuanian Culture Institute (LCI), particularly Rūta Nanartavičiūtė for getting the exhibition to India, was a great experience. We brought our own histories of reading and publishing children’s literature from the Indian context to the exhibition, and designed a couple of panels featuring Soviet books in Indian languages.

When the exhibition opened at Tara Books in 2014, Giedrė of the LCI was brought in as a curator–speaker, courtesy of the LCI. Spending time with her, I was taken in by her erudition and her critical yet generous understanding of her country’s (Soviet) cultural past. In discussion with Gita, we decided that we would work on a book project featuring the exhibits, along with a set of extended essays. In the planning, discussion and dialogue over email, the book grew into a large history project – and we realised we were actually suggesting another perspective to the history of the children’s picture book, with the Soviet Union as its hub.

Giedrė: When I came for a visit to Chennai from Lithuania and joined Geetha for the preparations of the opening of the exhibition at the Tara Book building, I realised that I was among like-minded people – much more than elsewhere. We had so much in common in terms of themes to do with and after the exhibition that it seemed a shame to stop with the latter, and with the memory of its wonderful opening day. And so that’s how we came up with the idea of the book. The authorship of this idea belongs to Geetha; however, the book is unimaginable without Gita Wolf’s participation – Gita is the founder of Tara Books, and also the motor that drives the publishing house.

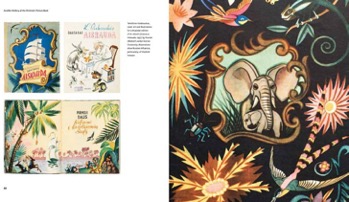

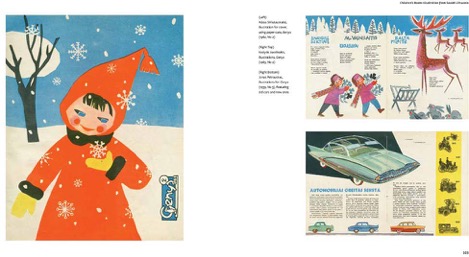

Why was Tara Books interested in Lithuanian children’s books of the Soviet period? There could be two reasons from my point of view. First, Tara Books is known for publishing interesting and very beautiful handmade books, but it also specialises in and has a history of working with graphic design. In fact it has a very particular approach to this subject – and if we are to speak in art theory terms, this could be attributed to the approach of social art history, focused on the interrelationship between art and society. The second reason is the popularity of Soviet children’s books in India in the second half of the twentieth century and the importance of this phenomenon. This last was a surprising discovery for me, and I guess would be for many people who have no experience of Indian everyday life of this period. India was a territory of special interest for the Soviet Union then, and it wanted to expand its sphere of influence there. And, for this purpose, and along with various other efforts, the Soviet Union made available children’s books in English as well as in Indian language translations – sometimes the print runs for these books went into the 1000s. They also cost only a few rupees and were sold in the streets.

This is why we have ‘a story’, written from two different perspectives, the Indian and the Lithuanian. So you have two different experiences of contact with Soviet culture, and the exercise has been very interesting and illuminating for both of us.

Lithuania and India–one would not immediately link them together. How have you managed to weave the stories since you are each coming from a different background/perspective. What are the common links? What are the differences?

Geetha: I think I have answered part of the question above. How did we put our narratives together? Well, for me, the book project was exciting and important because it had the potential to bring together two aspects of a cultural history as it unfolded in the Soviet Union over several decades. One part of the story, and an extremely well-researched one, was what Giedrė had to tell. And this has to do, as readers of the book know, with Soviet cultural policy and how Lithuanian publishers, authors and artists engaged with its changing and unchangeable features – particularly with respect to children’s books. Giedrė treats these books as important cultural productions, and places them in the context of a complex political and cultural legacy – and in the event tells a great story of children’s book publishing, illustration and design in Soviet Lithuania, which is also a story of culture as such.

Ultimately what holds the book together is a shared commitment to the children’s picture book. As publishers of children’s picture books and illustrated books for adults, we value the visual as much as the word, and believe that pictures communicate in radical ways – challenging not only how we see, but also our understanding on that account. To us, doing this book has meant tracing our own genealogy as publishers who look to an interlinked world for inspiration.

Giedrė: As Geetha pointed out, our book is not just about illustration and children’s’ book art. It is also about publishing politics, and culture politics in general, about ideology and censorship, the reception and perception of literature, of reading and evaluating practices, and of attempts to expand the borders of imagined, literary worlds and, by implication, the borders of the real world that were narrowed and restricted under pressure from the politics of the Soviet state. So, in this sense, these are not local issues at all, and since we are both deeply interested in these issues, it wasn’t difficult for us to weave our stories.

On the other hand, our common concerns notwithstanding, each of us came to them from different angles, from our own historical perspectives and personal experiences. While in Chennai, in and through our conversations, Geetha and I realised that there were many intersecting points to our narratives, and that this would make for a successful collaboration. I’d like to add one more thing. Talking to Geetha and Gita and to Indian visitors to the exhibition, I realised that they actually understood what I said about Lithuanian life, culture and art under the Soviet regime – more than other people like them who lacked these experiences. I felt encouraged on this account to go ahead with our project.

Geetha: Most accounts of the evolution of the children’s picture book, at least in Anglo-America and western Europe, look to mid and late nineteenth century developments to do with publishing, printing, the evolution of illustration as a profession in its own right, shifting notions of childhood, children’s taste, suitable reading for children and so on. While nuanced accounts point to other linkages, including with the early twentieth century avant-garde, when child art became a topic of debate and dissection, these seldom help illuminate what was afoot in the world beyond Europe and America.

Our project unsettles this understanding – and points to how we may tell another and equally important story of the children’s picture book if we look eastward and take seriously the logistically complex and enormously ambitious Soviet publishing enterprise that put out books in a hundred and more world languages, and which catered to children in west Asia, parts of Africa, South-East Asia, China and South Asia. We suggest the outlines of such a history by looking at two specific geographies and histories, one that has to do with places within the Soviet Union and the other outside the Soviet Union.

Giedrė: I agree with Geetha that very little research has been done with regard to the immense world of modern children’s books beyond the English-speaking countries. I hope that through this book we have managed to show that it’s worth looking at what has happened in other continents and countries. Importantly, the book also shows that this world is not so fragmented as it appears at first glance. I don’t want to go into the details – except to point out that we have so many children’s heroes in common. This then means that we share not only stories, but also values that are expressed by these stories and that we are connected across our different contexts. I would imagine it would be very interesting for people to know about how their favourite children’s-book characters, such as Lewis Carroll’s Alice, Tove Jansson’s Moomins, Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking and A. A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, and to go beyond books, e.g. Disney’s Mickey Mouse, fared outside their original worlds – and how they brought much joy and colour into the grey and gloomy world of thousands and thousands of children who lived behind the Iron Curtain.

Geetha: For my part, this is very little studied in the Indian context – the world of Soviet children’s publishing and how that brought books to our shores, and what that did to our local literary cultures. While establishing this connection with very broad brushstrokes for this project, I realised that we need to do a lot more research, especially of influences on Indian children’s publishing, on authors, artists, on attitudes to do with the children’s picture book, etc.

Giedrė: We had very good artists illustrating children’s books during the Soviet period. So, for a long time research focused on their art, on the development of their individual styles and the connections their art had with the international avant-garde. For many of them this connection was important, since it represented an attempt to resist the pressure imposed on artists during Communist rule. But it became clear that we needed to do more. While preparing for the exhibition in Bologna in 2011, we had actually widened our perspective on how we wished to frame children’s illustrations, but it was Geetha who inspired me to pay more attention to some other aspects of publishing in Soviet times – e.g. the publication of translated works, the distribution of commissions among artists and the impact of these developments. For instance, books by foreign authors when published in Lithuanian featured the original illustrations and this proved very stimulating to local artists, and also defined different aesthetic criteria for their readers, both children and theirparents.

Also Geetha suggested that I think and write more on the people who were behind the publishing in all its various stages. As I went about addressing these questions, I came to discover new things about people whom I thought I knew, but clearly I did not know them well enough. But these are yet initial steps in that direction, and a lot of work needs to be done before we understand better and can explain with some depth the phenomenon of the children’s book in Soviet culture, and, as we show in our book, its complex, multifaceted character.

I’ve mentioned Mickey Mouse earlier, and for children in Lithuania he seemed an icon of early Western pop culture. While working on our book I found out that such elements of children’s pop culture circulated in other ex-socialist countries as well – books and cartoons, which had nothing to do with ideological clichés, circulated across a wide area, from Czechoslovakia to Cuba and from Poland to Angola. Of course, if we want to describe that phenomenon, we should look at the children’s book primarily as a political phenomenon and not only as an aesthetic creation.

How did you collaborate? Did you write your theses separately or did you work closely together? Did this produce surprises? Was it easy to write?

Geetha: We wrote our essays separately. And the book falls into two parts, with the first and shorter part to do with Indian developments and concerns, and the second and longer part to do with Soviet Lithuania. But we worked closely together nonetheless, reading each other’s scripts and poring over the art. The surprise in all of this is the Soviet Union – its unreality so to speak, that it had these various faces, and how often one face was unaware of the other.

Giedrė: Unfortunately due to the distance between Vilnius and Chennai and the high travel costs we had no choice but to work separately. Of course, the long conversations that we had when I was in Chennai in July of 2016 proved very helpful. We started out with me sending Geetha an initial draft of my text and she responded with a long list of questions. I took off from those questions and it made my task easier because all I had to do was answer them!

Why do you think this approach is important? Do you think there are other are as within the picture-book world where surprising juxtapositions might be discovered?

Geetha: Comparative studies, I think, are very important because they free us from our own immediate culture areas and help connect our concerns with comparable ones elsewhere. However, having said that, I think we need to be precise and historical about what we wish to compare – in other words, we cannot bring about surprising juxtapositions at will, rather we need to travel down historical paths that are interlinked, and to find out what paths link and how it is exciting. With respect to the children’s picture book, I think there is more that needs to be done, both within the various regions of the Soviet Union, and also the relationship that each of these regions had with places and histories outside the Soviet Union. Likewise, in Africa and Asia, where childhood as we understand it today did not exist until a few decades ago, we need to also link backwards to traditions of storytelling and art that addressed children and adults, and understand how these have been carried forward in time, and have been refined or changed by influences from outside our contexts.

Giedrė: This book proves how important children’s books are or can be; how new things come into our lives and cultures through children’s books. But the problem is, however crucial, childhood constitutes just around one fourth of an average human life. We live out our time as adults for much of our lives, when our problems seem large, the questions we have appear complex and we are caught up addressing them. This is perhaps why we accord children’s literature, rather research to do with children’s books, somewhat of a marginal place in general cultural history. But if we bring a fresh perspective to children’s books, adopt the comparative method and also approach these books from the point of view of social-culture theory, this might result in something new – i.e. we might be able to change the way we see children’s books habitually as occupying a lower rung in the cultural hierarchy.

Giedrė Jankevičiūtė is an art historian, critic and exhibition curator based in Vilnius, Lithuania. The main area of her professional interest is Central–East European art of the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. From 2010 she started to research the history of Lithuanian graphic design and published several books and catalogues on the subject. Among her publications on graphic design are: Illustrarium: Soviet Lithuanian Children’s Book Illustration (2011), Okupacijos realijos. Pirmojo ir Antrojo pasaulinių karų Lietuvos plakatai [The reality of occupation: The poster in Lithuania during WWI and WWII (with Laima Laučkaitė, 2014) and Telesforas Kulakauskas (1907–1977) (2016). She is a member of the Lithuanian art historians association (AICA), the European Network for Avant-Garde and Modernism Studies (EAM) and the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS). Bibliographic details of the book discussed: Another History of the Children’s Picture Book: From Soviet Lithuania to India (with V. Geetha, Tara Books, Chennai, India, 2017; also in German: G. Jankevičiūtė, V. Geetha, Eine andere Geschichte des Kinderbilderbuchs. Vom sowjetischen Litauenbis nach Indien, Tara Books, Chennnai, India, 2017).