Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales by Katherine Langrish

Judith Philo

This book of essays emerged from Katherine Langrish’s many years of posting a blog on fairy tales, folklore, fantasy and children’s literature. When I read the title, boldly printed in capital letters an involuntary shiver went through me.

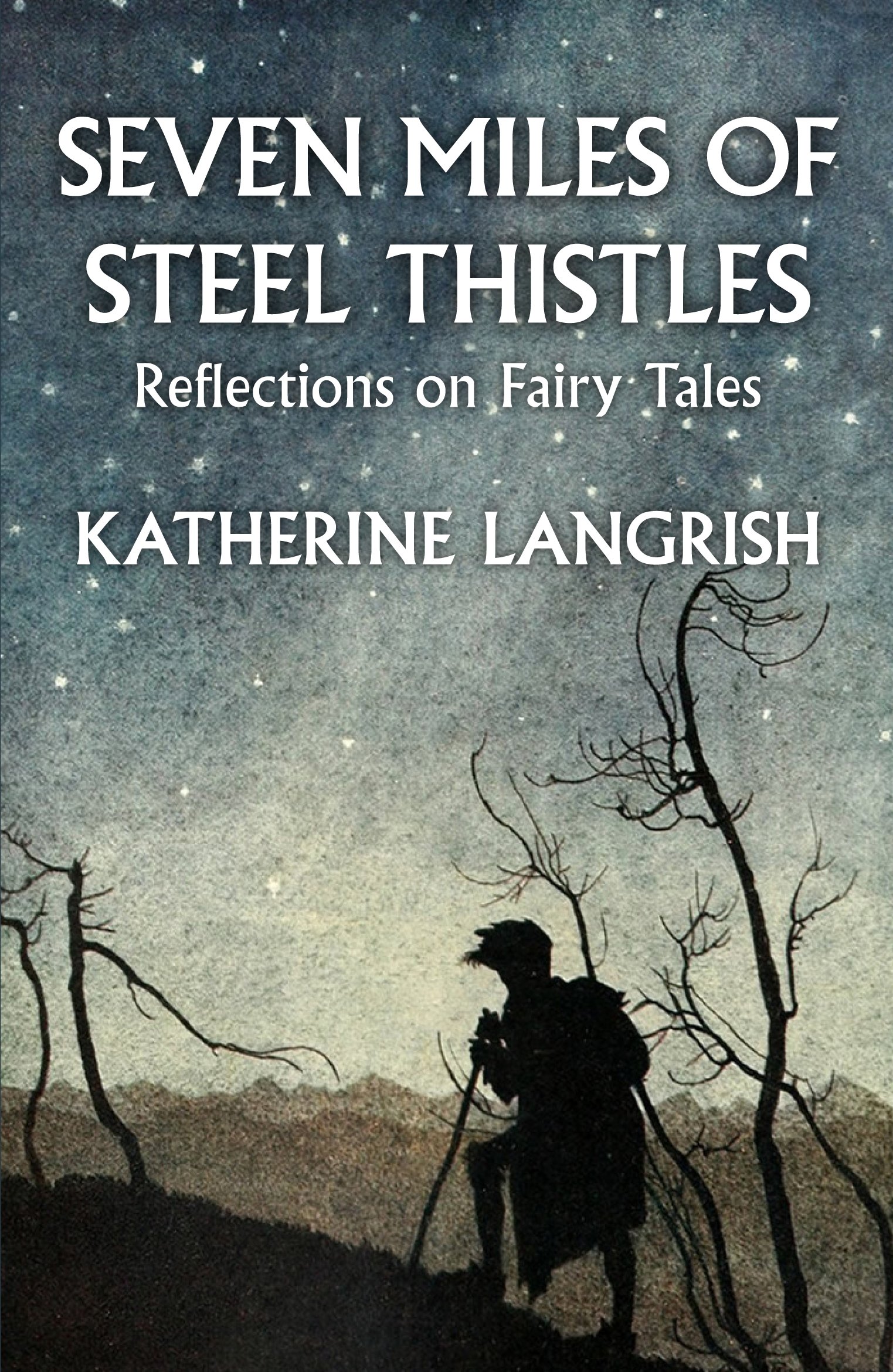

An arresting title, then, with a sense of menace, but modified by the phrase ‘Reflections on Fairy Tales’, making space for thought. The author’s name, in bold print, firmly positioned just below. All this imposed on a wash of grey night sky illuminated by a multitude of stars. In the foreground the silhouette of an elderly traveller resting on his stave looks outwards, as he pauses on a hillside whose sparse vegetation is bare branched trees. The landscape beyond is of mountain ranges stretching far into the distance. This figure, with his backpack, could represent the eternal wanderer who collects and disseminates stories from many different lands as he travels the world. He may be looking at the stars to chart his way or to find his destiny. Another familiar embodiment of the storyteller is the figure of a woman with the household gathered round her as she spins or weaves. Safe at home the listener can be transported in imagination to adventures in other dimensions and worlds.

In a comprehensive introduction Langrish develops her thoughts on the differentiation between types of story: ‘Myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it’; ‘legend recounts the deeds of heroes’ (p.5). Folktale is a local affair: some characters may be recognisable, but the landscape is the main feature of the narrative.

This could be the report of a sighting of a phantom army where a real event occurred, such as the violation of the community by soldiers. Such a traumatic experience may then be recorded by the local population and succeeding generations in their collective memory.

We are halfway through the book before we learn the origin of the title. The circumstances of its discovery also offers us a clue about Langrish’s interest in fairy tales. ‘The King Who Had Twelve Sons’ contains the phrase chosen. It appears in extended form like an epigram on the title page, ‘There are seven miles of hill on fire for you to cross, and there are seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea.’ Langrish found the story in an old book in a second-hand bookshop: West Irish Folk- Tales and Romances collected and translated by William Larmine, published in 1893, reviewed and praised by William Butler Yeats.

Old books have personalities and so I shall describe it: spine bound in red cloth with gilt lettering, boards covered in green cloth with a gilt medallion on the front cover, pages a little drunken and furry-edged, stitching loose. (p.146)

William Larmine was a minor Irish poet and folklorist who spoke Gaelic. He collected and translated stories from named oral storytellers. Langrish describes reading his account of being told the story which she shares with the reader, ‘a simulation of actually being there and listening to the storyteller: it’s picaresque, free moving, and full of minor inconsistencies’ (p.149). The twelfth son has to roam the world to find his destiny; he encounters and overcomes dangers and fulfils assignments; he wins the hand of a princess, but further complicated quests await him. Suddenly the narration breaks off as the teller falters in his account of further intricacies of the plot and counter-plot. Wait, he remembers the tale’s last sentence: ‘when the first wife saw the second wife … she could esteem herself no longer, and she died of a broken heart’ (p.155). I suspect that Langrish was captivated by this story before the occurrence of the sudden downbeat anti-climax. Such an experience for the listener is valid she concludes because ‘the good of it … demonstrates the process by which all fairy tales have come down to us’ (p.156). Fairy tales on the written page remain static, preserved in time, whereas the fairy tale told aloud is infused with the liveliness of the moment, they ‘belong to the person who is telling them, for as long as they are upon his or her tongue’ (p.156).

The book’s contents are divided into four sections, the first is On Fairy Tales, which includes the introduction and is followed by essays which explore a theme that is common to several stories, like ‘Fairy Brides (and Bridegrooms)’, and overall focuses on the many facets of the role of women in fairy tales. These essays are interspersed with Langrish’s own acutely observed poems ‘After the Wedding’, ‘Naming the King of the Fairies’, ‘Consulting the Yellow Dwarf’. The section Reflections on Single Tales follows. These are close readings of six stories, full of insight, two of which are not well known: ‘The King Who Had Twelve Sons’, from which the book title comes, and ‘Bluebeard, Mr Fox and the Bloody Chamber’. This essay compares the story of Bluebeard, which comes from Perrault, and which Langrish dislikes intensely ‘a nasty, charmless piece of blood and thunder’ whose effect rests on ‘how much the reader or listener can enjoy the voyeuristic suspense of wondering if or when Bluebeard’s wife will die’ (p.198) with the old English fairy tale ‘Mr Fox’ (quoted in Much Ado About Nothing we are told (p.203)). The heroine of this tale, Lady Mary, ‘is resourceful, brave and intelligent’ (p.209), whose curiosity saves rather than endangers her. Declaring that she would never tell the story of Bluebeard to children, Langrish informs us that she does tell the story of Mr Fox to school children of eight to ten who are always gripped by it.

However I don’t think she allows for psychic manifestations that violent and traumatic events may trigger within individuals and communities and haunt them for generations if appropriate recognition of such events has not been formally acknowledged. An event will remain pointless if it remains beyond the reach of symbolic thought.

In an earlier essay, ‘Desiring Dragons: The Value of Mythical Thinking’, Langrish makes us aware of the relevance of symbolic thinking to the enduring power of myths and fairy tales in the last essay of the first section On Fairy Tales. She asks in response to the scientist Richard Dawkins, who has questioned their value, whether we should be expected to outgrow such tales. (It seems ironic that Dawkins, known for his work on the gene, the replicating entity on our planet, has defined another entity, the meme, which he calls a ‘unit of cultural transmission’ (Zipes 2006: 4). I think we would recognise this applies to myth and fairy tale). Langrish asks questions about what impression ‘art’ makes on us, what does it give us, does it change us? At one point she says ‘I want to know what lies beyond the boundaries of my five senses’ (p.117). We are human and have the capacity to use tools, also to think symbolically. In developmental terms, the care we receive in infancy enables us to develop the capacity to trust and to imagine. These are precursors for our capacity to play, which in turn facilitate our emotional and intellectual development. Fairy tales and myths contribute to our pleasure in playing, which offers us opportunities to experiment, to learn from experience not from only our successes but from our failures also, all of which contribute to the possibility of living creatively.

In her final section Envoi, ‘Happily Ever After’ Langrish celebrates the art of oral story telling. It is clearly a role that she relishes. She describes the framework necessary to gain and hold the attention of an audience from beginning to end by the playful use of language, facilitating an atmosphere of make believe, creating a space to play imaginatively, and from which listeners can be released at the end. (Those people who came to the November 2017 IBBY UK/NCRCL MA conference ‘Happily Ever After: The Evolution of Fairy Tales across Time and Culture’ will remember how memorably the conference ended as Sally Pomme Clayton enacted the Russian story of Baba Yaga. It was a thrilling and exhilarating conclusion to the day). Langrish bids her readers farewell with a lengthy flourish in an ebullient flow of nonsensical phrases and images, leaving one with a strong sense of wanting more, and with an expectation born from a good experience that this can be found again. For by now we know that fairy tales are for everyone: children and grownups too.

The strength of the book lies in Langrish’s deep knowledge of and exploration of tales, many of which I was not familiar with. She reminds us of their perennial relevance as a source of personal and cultural enrichment. I recommend it wholeheartedly.

Works cited

Langrish, Katherine (2016) Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales. Carterton: The Greystone Press.

Zipes, Jack David (2006) Why Fairy Tales Stick: The Evolution and Relevance of a Genre. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.